The standard rating nomenclature for GO, world-wide, is Japanese in origin. It begins with "30-kyu" [30 K'yew], for complete beginners, and proceeds upwards to "1-kyu", the most senior Intermediate Amateur rating. Advanced Amateur ratings begin at "1-Dan" [1 DAWN], and proceed further upward to "9-Dan". The principal purpose of ratings is to facilitate setting proper Handicaps between players of different skill-levels. Ostensibly, the difference between two players' ratings is the number of stones the weaker player should place on the board, as Black, before the stronger player may place the first White stone, i.e., White's appropriate Handicap. This is to ensure that both parties may enjoy an equivalent challenge from the contest, and thereby a comensurate potential for growth.

In the Amateur ranks, each level represents a degree of playing ability sufficient to overcome Black's first-move-advantage (worth about 13½ points), while playing as White without Komi compensation, in more than two-thirds of such matches against an opponent one rating level lower. For example, a person rated at 9-kyu should be able to play White against a person rated 10-kyu, and win more than twice as often as the Black player despite the lack of Komi. That difference in skill level between local ratings is generally quite accurate; however, in the global GO community, not all 5-kyus or 6-Dans are the same strength—any given 7-Dan living in Japan may only be as strong as a typical 5-Dan living in China, simply because of the scale of the local population with which that player regularly contends. However, with the advent of online GO the standard deviation of ratings world-wide is diminishing. Online, ratings are generally abbreviated as 30k through 1k, and 1d through 9d. A person's online rating will naturally fluctuate downward as a new phase of learning is being assimilated and gradually rise to a new high point where it will plateau for a while until another learning phase begins.

Curiously, Professional Players are ranked (not 'rated') in a parallel system from 1-Dan to 9-Dan, but the strength differences between rankings in the Professional spectrum are only one-third of a stone; but, a 1-Dan Professional is approximately equivalant in strength to a 7-Dan Amateur. Online, it is common to abbreviate professionals' Dan-ratings as 1p through 9p—the 'p' meaning '(Professional)-Dan'. Demotions within the Professional Ranks practically never happen.

When an un-rated player meets a new opponent, it is usual for the game to be played without handicaps, and then either to estimate a handicap for subsequent games, or use a result-method to adjust the handicap incrementally according to the player's performance. If one of the players has a rating, the other player's rating may be (provisionally) set relative to it. All ratings are initially set in a similar manner; however, the accuracy of such ratings are proportional to the number of other people against whom the rated player has demonstrated a similar relative ability. So, it stands to reason, that the more often one plays, and the larger one's circle of similarly rated opponents is, the more likely it is that one's rating will be accurate.

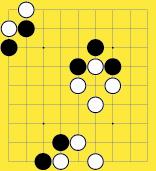

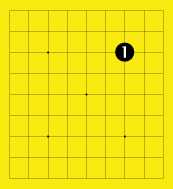

![Figure 3: Black 1 is in Atari. Playing Black 7 immediately below it forms a group of two stones with 3 liberties. [click] Playing anywhere else with Black 7 permits White 8 to capture Black 1.](IM_Figure3a.jpg)

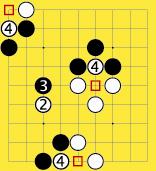

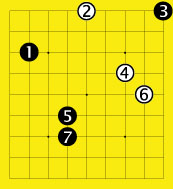

![Figure 4: The marked White stones are in Atari. A Black or White stone at 'b' will capture or connect [click] the White group, respectively.](IM_Figure4a.jpg)

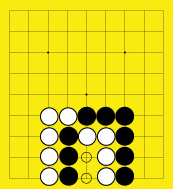

![Presuming it is Black's turn, here are 3 examples of initial positions with analogous Ko potential. For the purposes of demonstration consider each of them to be isolated instantiations (since only one [numbered] stone of any colour may actually be placed per turn).](IM_KO_animated3.gif)